Organisational culture is a colourful creature that divides opinion. On the one hand, there is the conviction that culture can hardly be changed, if at all. From this perspective, we have to accept it like the climate zone in which we live (and where this is unsatisfactory, the good old Hamburg saying „There is no such thing as bad weather, only the wrong clothes" applies).“).

On the other hand, there are sophisticated design approaches of the Cultural Engineering, which pursues the change of formative patterns of thought and action through systemic interventions, and the Transformational leadership, which places alignment through values and visions at the centre. In many cases, the „transformative power of symbols“ is relied upon: Raise new flags, bring new stories into play, conference table out, ball pool in and lo and behold: a new culture grows on the breeding ground of such artefacts.

That simple? The history books make it seem simple, because in the 4000 years of organised leadership practice we find hundreds of examples of such transformative change - an impressive case. What we don't find there are the millions of cases where cultural change came through the back door. If we use the front door as a stage for transformation, we need to make a robust entrance. The problem with robust performances is that they exclude sensitivity in a way. Proclaiming and listening are not easy to reconcile. But if listening is important in order to understand the underground, the back door could be an interesting alternative for cultural change.

My first encounter with the metaphor of guerrilla gardening in the context of organisational development was in 2011 at the „oe-tag“, a specialist conference that SOCIUS organises annually in Berlin. The conference focused on questions of organisational culture. In their workshop, two colleagues, Anna Krewani and Kerstin Giebel, presented a subversive approach to cultural development, the core idea of which is: instead of changing culture with grand gestures from above, look for the peripheral spaces of the organisation and establish practical examples of the desired future there that radiate and inspire. Beautiful little things - flowers in the concrete. I have played and experimented with this idea a lot in recent years, have been both enthusiastic and frustrated and am now a firm believer.

The roots of guerrilla gardening lie in appropriative spatial development. The following instructions from reset illustrates the simple basic principle of the approach in urban practice:

- Find an unkempt peripheral piece of land, a wall, a tree - preferably in your own neighbourhood.

- Decide what you want to plant and check whether your choice makes sense. Robust plants and fast-growing flowers are a good start.

- It's more fun together - find a partner. Talk to friends and neighbours.

- Build your garden. You may need to bring some fertile soil and be sure to water the plants after planting.

- It may be advisable to protect your garden from the challenges of city life, possibly with an improvised small fence against dogs and feet.

- Tend your garden with love! Go regularly and water it.

- If things don't go as planned, don't be discouraged! Talk to the residents! Most of them are on your side and will at least give you moral support. Some may even join you!

(Source: reset.org)

The guerrilla gardening principle in organisational development

I don't think I need to translate this little guide into OE language - the transfer is easy. And yet putting it into practice in the development of organisations is anything but trivial. First of all, it requires a lot of patience.

One of my first experiences with the approach was in supporting an educational institution with 50 employees. The culture of the organisation was characterised by mistrust and fear at all levels and we were asked to establish a new quality of leadership and cooperation as part of a mission statement development. We presented the concept of guerrilla gardening to the management team: A joint kick-off to collect points of pressure and suffering; exploration of recurring patterns and underlying imprints; and finally: formation of small groups to develop decentralised experiments in a new culture of collaboration. Despite some scepticism, the proposed approach was accepted. We were confident and ready for a small miracle.

The process of discovering dysfunctional patterns and possible building blocks for a positive future gained momentum. But when it came to developing the guerrilla gardening initiatives, the process got a little stuck. People were disappointed by the scale of things: a regular team picnic in the park, a working group exploring new conflict resolution strategies, a feedback questionnaire on experiences of good leadership practice - the ideas seemed like pinpricks; some of the plants withered, some were trampled; and yet some survived. It was only much later that we realised how much the process had helped us all to better understand the patterns, the difficulties and the visions in the organisation. A second loop led to even better results, the initiatives became bolder and received more attention. In the third year, the organisation formulated a new mission statement, which was not about presenting politically correct buzzwords, but about outlining the inherent problems that the team and leadership were committed to tackling in their work together. The culture had changed - not through centralised proclamation, but through small, harmless experiments on the periphery.

What happens then? How does the experiment change the whole system?

The Guerilla Theory of Change exists in a number of versions.

Germ form - lessons from neo-Marxism

Neo-Marxist theory has coined the term „germinal form“ as a social practice that operates within the functional logic or „grammar“ of the dominant system, but undermines its social logic and value base. Peer commons and share economies are examples of this: they function smoothly within the market logic of supply and demand, but undermine the idea of private ownership of the means of production (at least that was their claim at one time). When they emerge from their niche in a crisis of the dominant system, they have the potential to transform into dominant practice - the process for this leads from a change of function to a change of dominance to a complete restructuring of the system. In the organisational context, agile models can be described as such „Trojan horses“, as they function under the assumption of lean and efficient management and at the same time introduce approaches of self-organisation and autonomy (of course, this is a double-edged sword: it is also possible that agile methods are imported with the aim of strengthening self-management and in doing so build up new pressure to perform „as a side effect“).

Neo-Marxist theory has coined the term „germinal form“ as a social practice that operates within the functional logic or „grammar“ of the dominant system, but undermines its social logic and value base. Peer commons and share economies are examples of this: they function smoothly within the market logic of supply and demand, but undermine the idea of private ownership of the means of production (at least that was their claim at one time). When they emerge from their niche in a crisis of the dominant system, they have the potential to transform into dominant practice - the process for this leads from a change of function to a change of dominance to a complete restructuring of the system. In the organisational context, agile models can be described as such „Trojan horses“, as they function under the assumption of lean and efficient management and at the same time introduce approaches of self-organisation and autonomy (of course, this is a double-edged sword: it is also possible that agile methods are imported with the aim of strengthening self-management and in doing so build up new pressure to perform „as a side effect“).

Niche-regime interaction - lessons learnt from transition management

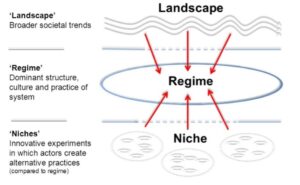

A second way of describing the impact of local experiments is the niche-regime interaction presented in Transition Management - a framework that was developed in the context of the sustainability discourse to describe the dynamics of the „Great Transformation“. The multi-level perspective of the transition management model comprises three interrelated system levels:

Image: J. Broerse, VU University Amsterdam (https://slideplayer.com/slide/9791473/)

- the landscape level (macro: broader social trends and the relevant system environment),

- the regime level (meso: dominant structures, cultures and established practices of the system itself) and

- the niche level (Mico: experiments and innovative alternative practices).

Transition management assumes that regimes function with an evolutionary logic, filtering out unsuccessful experiments and gradually selecting useful innovations and integrating them into their existing practices. Niches are safe environments in which such innovations can grow, protected from the selection process. The pressure from the landscape is the key factor in how receptive (or susceptible) the regime is to niche innovations (will the innovation complement, repair, titillate or disrupt the regime?). Moments of high receptivity are windows of opportunity in which radical innovations can become drivers of change. If they accumulate to a critical mass and are aligned across different subsystems, they can transform or even replace the regime (F. W. Geels, J. Schot / Research Policy 36 (2007) 399-417).

The guerrilla gardening approach can be analysed through the lens of this model as niche-regime interaction. In order to be more effective as an impetus for change, three conditions must be met:

- The local experiment must be protected from performance and control pressures long enough to become a coherent new model practice with a „proven“ veneer.

- The moment when the new practice is presented as a model solution must fall within a window of opportunity (e.g. an established practice no longer provides answers to a new challenge or external pressure).

- The new practice must be integrated and accumulated with other innovative practices in order to create a critical impulse for the transformation of (at least part of) the system.

Two Loops - Lessons from Living Systems Theory

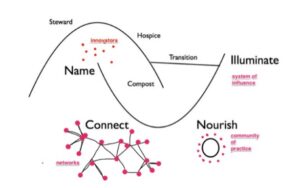

Another map of system change that fits with the guerrilla gardening idea is the Two Loops model developed by Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze at the Berkana Institute. The model describes the dynamics and roles involved in the transition from one system (in transition management terms: a „regime“) to another. Wheatley and Frieze assume that all systems go through a build-up phase, a peak phase and a decline phase - in larger social systems this may happen over a period of 250 years, while in organisations episodes that are characterised by a certain paradigm may only last a few years. Picture: Berkana Institute

Another map of system change that fits with the guerrilla gardening idea is the Two Loops model developed by Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze at the Berkana Institute. The model describes the dynamics and roles involved in the transition from one system (in transition management terms: a „regime“) to another. Wheatley and Frieze assume that all systems go through a build-up phase, a peak phase and a decline phase - in larger social systems this may happen over a period of 250 years, while in organisations episodes that are characterised by a certain paradigm may only last a few years. Picture: Berkana Institute

A system at the beginning of its life cycle is maintained by „stewards“. Under the cover of its heyday (in transition management language: in the „niches“), pioneers emerge who drive innovation. If these islands are connected and strengthened, they form the breeding ground for a new system. Its rise can coincide with the decline of the old system (as seen in the aftermath of the Roman Empire: not always a pretty sight). Hospice and composting work is required to prevent the old system from simply collapsing and disappearing. To ensure an orderly transition from the old to the new regime, the landing sites of the new system must be illuminated and the orderly relocation managed.

In organisations, we experience the Two Loops dynamic in times of environmental disruption, but also in crises associated with phase transitions. For example, during the transition from the pioneer to the collective phase, the collective impulse emerges as a (sometimes rebellious, sometimes reformist) subculture, while the established leadership model may still be firmly in place. The progressive decline of the old and the strengthening of the new are intertwined processes that feed off each other. At some point, when the new model is strong and coherent enough to be trusted, the system is ready for the transition.

All three models are based on the assumption that impulses for change arise in the subsurface of the system. They also show that careful practices and adapters are needed so that these subversive impulses can unfold their transformative effect in the system at the right moment.

(Original and more on https://lost-navigator.net)