For organisational development, borrowing from other disciplines is the icing on the sensemaking cake: be it navigating between map and terrain in nautical science, the secret of creative flow in art, the interaction of self-healing and treatment in medicine, or the development of operating systems and apps in software engineering – each image opens a different window and a different perspective on the organisation. As Gareth Morgan has impressively described, all metaphors are always helpful and inadequate at the same time.

The organisation of the city

For me, some of the most exciting sources of inspiration for OE lie in urban development. The interplay between design and the momentum of a city is a fascinating dialogue. Cities and organisations are quite similar, especially in terms of this dual nature: they are structured systems of rules and resources, and at the same time organisms that develop and unfold according to their own logic.

From an urban planning perspective, this momentum often has an unruly side: you can draw up a land use plan and build transport infrastructure, but it is much more difficult to control how spaces and areas are actually used. It is almost impossible to control which types of people and companies move in and out, thereby causing growth, gentrification or decline in individual neighbourhoods. You can lay paths through a park, but only time will tell which paths people actually take. The same applies to organisations: you can appoint someone as a manager, but how do you ensure that he or she is actually accepted as a leader? You can build a knowledge database, but how do you get people to actually feed their knowledge into it? You can write a quality manual, but how do you make a process binding? All too often, the actual course of events deviates from the formal one. And there is a reason for that.

The duality of the structure

Imagine you are walking through the park. It is a sunny day and you have nothing else to do but get some fresh air. The paved path you are walking along leads to a junction with another path that you want to take. Normally, you would walk to the junction, turn the corner and continue along the new path.

Now imagine the same scene on a cold morning, you are on your way to work. You approach the crossroads and perhaps take a shortcut across the lawn at the earliest possible point – this is economical (which, incidentally, is not the same as „humane“). If you are the first and only person to take this shortcut, the grass will give way under your footsteps and spring back up after a few moments. If ten other people take this shortcut on the same day, a small earthy trail will become visible in the grass. This line acts as an attractor, an invitation for others to take the same path, and very soon a beaten track will emerge.

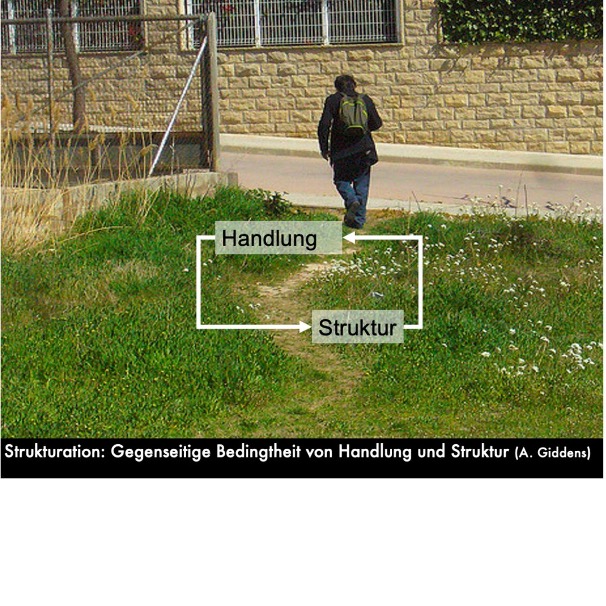

The mechanisms of this interaction are described by Anthony Giddens in his „Theory of Structuration“. Giddens locates social practices at the „inseparable interface between structures and actors“. In accordance with the recursive nature of social life, structures are both the medium and the result of the reproduction of social practices: the path is formed when the actors walk it. They walk it because its structural impact acts as an attractor. Giddens calls this the „duality of structure“.

The concept explains how social practices are reinforced and how this leads to the formation of structures (which ultimately solidify into formal institutions). It also explains how these structures are undermined when actors decide to ignore, replace or reproduce them in variation. Both movements take place gradually and fluidly. The model does not focus on a specific moment at which a rule or practice is formalised (or abandoned). All orders are provisional orders.

The blessing and curse of path dependency

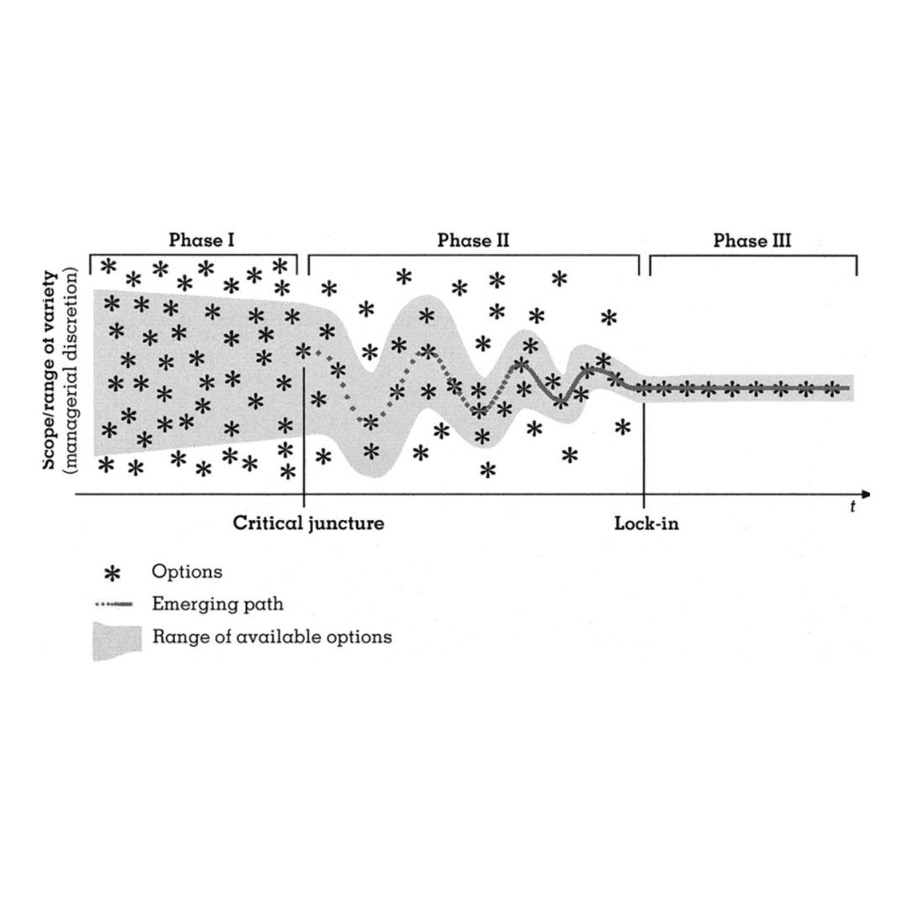

An interesting aspect of the emergence of paths is the interplay between individual and collective decisions. In a tabula rasa situation, in which a system has no meaningful substructure, no relevant attractors and no established interaction patterns, members act solely according to their individual agendas. In jazz, this is either cacophonous chaos or the moment when everyone waits to see what the others come up with. In group dynamics, this is the phase of Forming, in which uncertainty and a lack of common focus must be balanced by a clear external framework. Over time, the actors then develop patterns of interaction – in the best case, they „find“ a dynamic groove. The system forms substructures that confront its members as context. Some of the emerging patterns reinforce themselves, while others quickly disappear or are suppressed. In this phase, behaviour is determined both individually and systemically – the actors move according to their individual intentions, but are also influenced by the pull of reinforced patterns.

The moment when emergent patterns arise is so precious because it does not last forever. The development that follows is usually characterised by progressive path dependency, in which individual paths of interaction become increasingly entrenched. Patterns of action and thought that were just moments ago in dynamic harmony with one another form stable, dominant zones, development takes on fixed forms, and the system finds its riverbed and its flow equilibrium. In extreme cases, homeostasis becomes a „lock-in“ – the system freezes and solidifies. Anyone who has ever experienced such a lock-in at a jam session knows that fixation on a harmonic sequence can become a curse for players and audience alike, sometimes only broken by an almost violent modal break when someone can no longer bear it.

If we want to work with the forces of emergence in a frozen system, we must return groups and organisations to a state of relative openness and dynamic flow (phase II in the image above). There are two ways to achieve this: Either we wait until the system enters a crisis, breaks down due to its own rigidity and reassembles itself after creative destruction (a progression described in the Ecocycle); or we succeed in „thawing“ it, in the words of Kurt Lewin, while it is still in operation. Ideally, we establish a mode that never allows it to become completely rigid: Keep the ground soft.

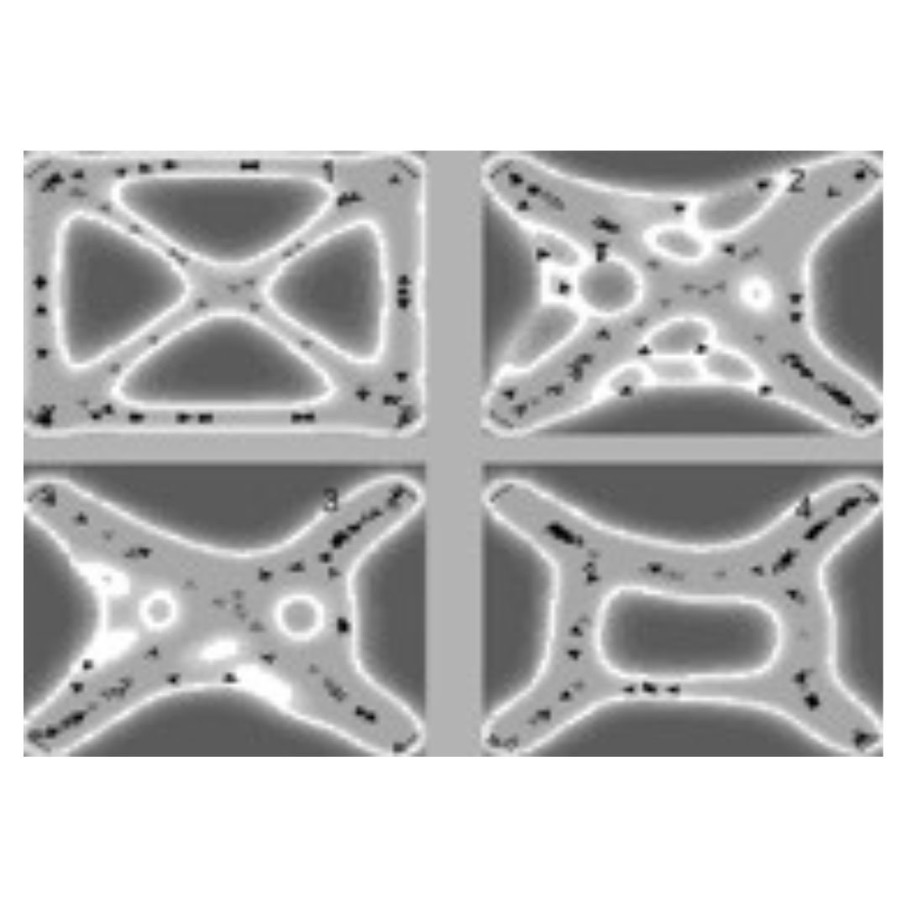

digressionCollective intelligence (or macro-intelligence, which is derived from local knowledge) thrives on the convergence of individually motivated behaviour and social feedback. A simulation sequence illustrates this relationship:

Image 1 shows a virtual park with intersecting footpaths. Computer-generated avatars (black dots) are programmed to follow random individual motives (e.g. walking from corner A to C; strolling to the centre, then walking to corner B, etc.). They also tend to follow paths that have been used frequently in the past. Use leads to the deepening of the respective path, while an unused path disappears over time. The effects of this programming can be seen in Figures 2-4. Over time, the path system transforms into a new, more compact form. For the individual avatars, the resulting path system in Figure 4 results in minimal detours. For the overall system, it represents an improvement on the initial form, as it is optimised in terms of total path length.

The simulation illustrates how individual actions, linked by direct or indirect feedback, can give rise to a collectively intelligent system.

Further insights on this topic can be found in Steven Johnson's „Emergence – The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software“.

The path as an expression of needs

The German word „Trampelpfad“ (trampled path) is a somewhat ugly term for an informal footpath. I much prefer the poetic English term „desire path“. It conveys the idea that every subversion marks a motive that the formal system has not yet taken into account. A desire path does not imply resistance to the formal system itself, but rather to a yet undiscovered potential of the system. A path should therefore not be a nuisance, but a valuable and welcome source of information for system designers.

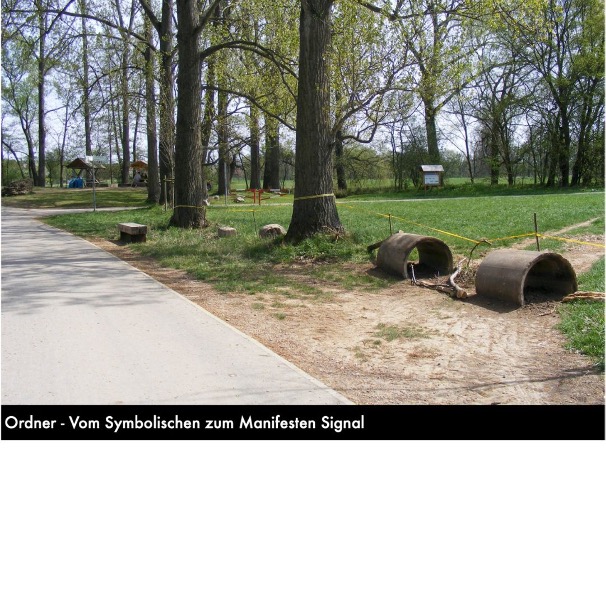

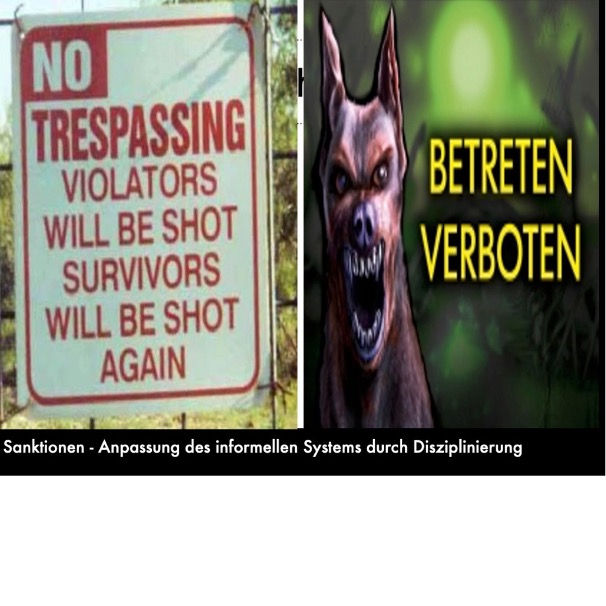

Back to the park: The parking service may not like you taking the shortcut across the lawn. So they put up a sign or a barrier. That may keep some people off the grass, but signs and barriers don't really work if a shortcut or attraction is strong enough. So they go one step further: they put up a fence or hire park security and reinforce the regulatory measures with sanctions. Regulation has a relatively low degree of effectiveness when it comes to unleashing intrinsic motivation and creative dynamics in social systems. It is also psychologically costly because it signals that this is not really your park. So why should you treat it with care?

Images: Applause for Design, Rienk Mebius

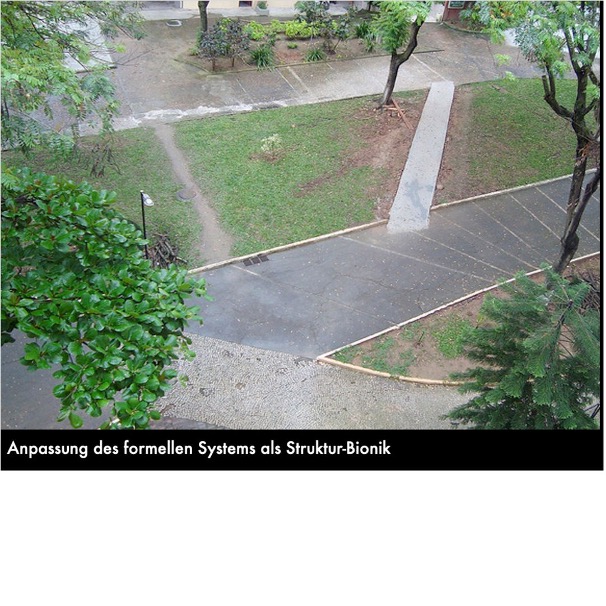

Alternatively, the logic can be reversed: just as technical developments in bionics are inspired by nature, it is also possible to conceive of „structural bionics,“ in which developers learn from behaviour mapped in paths. If dirt is repeatedly brought into the stairwell via an unpaved shortcut to the house entrance, a solution is required. However, the response does not have to be to get people to use the impractical paved access route. We can just as easily pave the shortcut to make it functional. The informal system thus becomes the anchor of the formal structure.

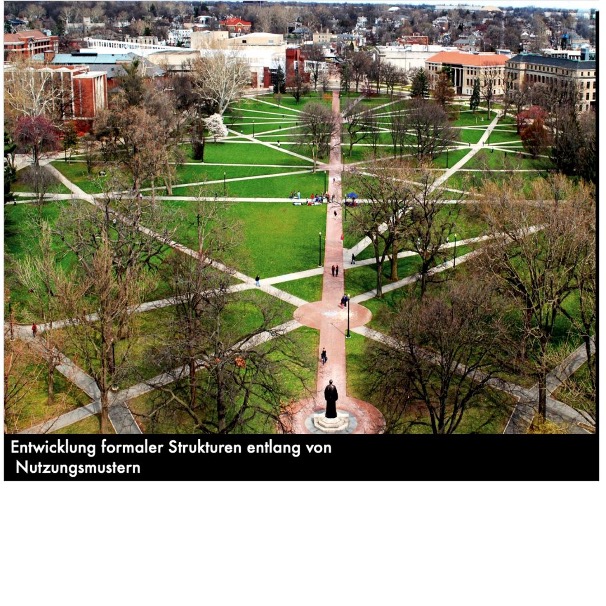

This design approach can also be applied on a larger scale: if you want to design a system of footpaths, wait a while to find out where people actually walk and then determine the formal path system based on these movements. Large campuses such as Ohio State University and the University of Toledo, parts of Central Park in New York, and some residential areas in Moscow were designed in this way (the latter by waiting for the first snowfall to determine where residents actually walk between buildings and entrances). Taking trampled paths seriously as an expression of needs can certainly yield meaningful results.

However, we can also overshoot the mark in the process. Unregulated emergence is particularly problematic in systems with multiple interests: not every development is equally beneficial to all members of the organisation, and not every impulse is compatible with the overall picture. Not every economic path is conducive to the overarching goal, especially if it is a shortcut whose costs have to be offset by others in the system. In this respect, emergence is not the only answer; we must take the task of curation seriously. This can mean creating overarching frameworks and containers in which the various impulses flow together into a meaningful whole. It can also mean finding transparent ways to weigh up and negotiate options against each other.

Desire Path practice in the OE

How can the desire path principle be applied to the field of organisational development? What concrete steps can we take to give this approach space to flourish?

The simplest version of structural development involves (re)designing the process for a specific task. The desire path approach to such process development can be described in five steps:

1. Mapping the formal structureIdentify the existing regulations (or also the Standard Operating Procedures) for the specific function or focused process (process descriptions, manuals, regulations on procedures and responsibilities).

2. Mapping informal processes: Conduct ethnographic and participant observations to understand how the focused process is actually carried out in everyday life.

3. InterpretationIdentify factors that motivate informal practices. Explain the discrepancies between formal regulations and informal practices (e.g. in relation to attractors and needs).

4. Assessment: Distinguish between functional and dysfunctional informal practices. Where is there a deviation from the formal structure that improves the result? Where do actors undermine the overarching goals of the system with informal practices? How can this be dealt with?

5. IntegrationEstablish a new formal structure that incorporates functional informal practices and offers viable alternatives to dysfunctional practices, taking into account the underlying motives.

This approach does not have to be limited to processes, but can be applied in a similar way to micro-political fields and role structures (who are the actual leaders?) or emergent strategies (what does the organisation really „do“?).

In any case, this turns the traditional approach on its head: it is no longer a question of how we can consolidate structures by regulating behaviour, but rather how we can design and establish meaningful structures by observing behaviour.

While a new formal structure found in this way will hopefully channel collective action better and more smoothly, it is also only a delicate seedling for the time being and, at the same time, only a provisional order. Classic organisational development focuses on the act of pointed formalisation. At some point, a decision is made on a model, and that seals the deal. It is entirely conceivable that this fascination with formal structuring misses the point: a structure does not come into being simply because we record it in an organigram. A structure exists when it is reproduced through repeated practice.

In my experience, most organisations seeking support in organisational development are willing to invest in the development of new structures, but assume that the implementation process will virtually take care of itself. The assumption behind this is that if employees are involved in the design process, they will take ownership and put their full energy into the implementation. While there is certainly no alternative to involving those affected by a development, participation alone does not guarantee smooth implementation. A supported process of practising new practices is needed. New paths must be established and may also change in the process.